Kenya’s election season is now in its final stretch. On August 9, 2022, voters across the country and members of the diaspora will go to the polls for another general election. Nationally, two leaders—Deputy President William Ruto and longtime opposition leader Raila Odinga—are facing off in a contentious race to succeed outgoing President Uhuru Kenyatta, who is finishing second and the -his last term in office. This election cycle comes at a time of significant economic discontent, with many Kenyans concerned about the rising cost of living, public debt, and widespread corruption. Given that Kenyatta is not up for re-election and that the country’s ruling coalition has broken up, Kenya will see a change in leadership regardless of the outcome.

Three important questions dominated the country’s election season. First, who will win the battle to replace Kenyatta as president? This is a particularly pointed question since the incumbent distanced himself from his current deputy (Ruto) and instead endorsed his longtime rival, Odinga. Second, the country’s electoral institutions, in particular the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC), will have the capabilities and credibility to manage a potentially close election and prevent the irregularities that ended the two previous election cycles? Third, how will the country’s current economic situation affect turnout and voting behavior?

Shifting Elite Coalitions

First, the 2022 elections and the battle to succeed Kenyatta show that Kenyan politics is still marked by unstable elite bargains that can reduce polarization in moments of crisis but also perpetuate inequality and weaken accountability for abuses of power. This may interest you : How to deal with workplace politics – Produces Blue Book.

In a sharp reversal from the past two elections, long-time opposition leader Odinga is entering the electoral contest as the de facto candidate of the establishment, with the support of the president and many of -political burdens of the country. In contrast, the deputy president Ruto—in power for the last ten years—led a successful campaign for foreigners, presenting himself as the only alternative to the “dynasties” that rule the country.

This unusual system is the product of a significant political realignment. In 2013 and 2017, Kenyatta won the presidency by forging an alliance between his traditional base in the central region of Kenya and Ruto’s stronghold in the Rift Valley. Odinga, whose Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) led an opposition coalition of small parties based in Kenya’s western and coastal regions, disputed the legitimacy of both elections, alleging widespread irregularities. Following a court-ordered do-over of the disputed 2017 contest, Odinga called on his supporters to boycott the vote and refused to recognize Kenyatta’s victory. The country has found itself polarized along political, ethnic and regional lines, sparking fears of violence reminiscent of the major electoral crisis that followed Kenya’s 2007 elections.

In 2018, however, an informal “handshake” agreement between Kenyatta and Odinga ended the standoff, paving the way for the political—and now electoral—cooperation of the two rivals. Together they created the Bridge Building Initiative, a series of proposed constitutional reforms framed as an attempt to avoid future electoral conflict. Critics, on the other hand, saw the move as a transparent effort to expand the country’s executive branch by creating new political positions. In May 2021, the High Court of Kenya declared the initiative unconstitutional, a decision confirmed by the Supreme Court in March 2022.

With Kenyatta formally backing his former opponent’s presidential campaign and ditching his own deputy, the ruling Jubilee Party has split. One faction is supporting Ruto, who is campaigning under the banner of a new political party, the United Democratic Alliance (UDA) and its wider Kenya Kwanza alliance; the other faction aligned itself with the Azimio La Umoja coalition of Kenyatta and Odinga.

This type of political realignment is a recurring feature of Kenyan politics (see table 1). Since the country’s transition to multiparty democracy in the early 1990s, electoral competition has generally revolved around loose coalitions centered around individual political leaders, who promise to deliver votes from their respective ethno-regional strongholds in exchange for political positions. and access to state resources. Because no single ethnic group enjoys an electoral majority in the entire country and Kenyan political parties are organizationally weak, political leaders often access power through personal bargains struck behind closed doors. These marriages of convenience tend to fragment once they have served their electoral purpose, as the recent disintegration of the Jubilee Party shows. In several moments of political crisis, this type of agreement has helped to reduce polarization: the Jubilee-led coalition that emerged in 2013, for example, brought together the two rival communities in the center of 2007–2008 electoral conflict, while the most recent agreement between Kenyatta and Odinga ended the rift created by the 2017 election.

Kenya African National Union (KANU) and the National Development Party (NDP)

KANU has been the ruling party since Kenya gained independence. In the run-up to the 2002 elections, he briefly formed an alliance with the NDP, then led by Odinga, although this coalition broke up before the votes were cast when it became clear that the then president Daniel arap Moi planned to endorse a young Kenyatta, rather than Odinga, as his successor. Odinga and his supporters (including disgruntled KANU members) went on to join the Liberal Democratic Party and form the National Rainbow Coalition.

NARC was formed when the National Alliance Party of Kenya, a group of opposition parties led by Mwai Kibaki, allied itself with the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) before the 2002 elections. NARC won a landslide victory, with Kibaki as its presidential candidate.

An alliance formed after the collapse of NARC, with Kibaki as its presidential candidate. It included several existing and new parties interested in Kibaki’s re-election as well as KANU (at that time the opposition party). Kibaki emerged victorious, although the elections were characterized by widespread political violence.

Building on a movement that successfully opposed the 2005 constitutional referendum brought by the Kibaki government, ODM merged into a political party with Odinga as its presidential candidate. Other notable members at the time included Ruto, former deputy president Kalonzo Musyoka, and former deputy president Musalia Mudavadi (although Musyoka later split to form his own ODM faction and contest for the presidency on a separate ticket ).

Coalition for Reforms and Democracy (CORD)

The Jubilee Alliance was founded to support the Kenyatta-Ruto presidential ticket. Kenyatta and Ruto had left KANU and ODM, respectively, and registered new political parties—the National Alliance and the United Republican Party. These parties then joined to form the Jubilee Alliance, along with what was left of the NARC.

The coalition included Odinga’s ODM, Musyoka’s new Wiper Democratic Movement Kenya, and former foreign minister Moses Wetangula FORD-Kenya, among others. He was in front of an Odinga-Musyoka presidential ticket.

After a merger of twelve parties (including the parties of Kenyatta and Ruto, who had previously joined the Jubilee Alliance), the united Jubilee Party faced Kenyatta and Ruto’s re-election bid .

The NASA coalition has once again brought together political parties led by Odinga, Mudavadi, Musyoka, and Wetangula, among others, to oppose the Kenyatta-Ruto 2017 re-election bid. NASA presented an Odinga-Musyoka ticket, like CORD in the 2013 election cycle.

Azimio la Umoja-One Kenya brings together ODM, the Jubilee Party, and one faction of the One Kenya Alliance (which includes Wiper, the National Rainbow Coalition – Kenya, and KANU). It has Odinga as its presidential flag bearer, with Martha Karua as his running mate.

The alliance consists of Ruto’s newly formed party, the UDA, and defectors from the One Kenya Alliance (ie Mudavadi’s Amani National Congress [ANC] and the FORD -Kenya of Wetangula), among other parts. Ruto is the presidential candidate, with Rigathi Gachagua as his running mate.

OKA consists of key political actors who initially intended to offer an alternative to the Odinga-Ruto contest. In its early formation, OKA included Musyoka’s Wiper Party, Mudavadi’s ANC, Wetangula’s FORD-Kenya, Martha Karua’s NARC-Kenya and KANU, among others. She has since split.

But the upcoming elections also highlight the limits of this political logic. First, weakly institutionalized coalition politics undermines democratic participation and inclusion. For example, political elites have repeatedly relied on insider negotiations to select candidates for important elected positions and used tactics such as zoning to avoid candidates competing with others from within their coalition. Although such decisions may make electoral sense, late and opaque decision-making by the parties and perceptions of favoritism have fueled discontent among party hopefuls. More than 7,000 aspirants are now running for office as independents, underscoring widespread distrust in the parties’ nomination processes. Women and other marginalized groups particularly struggle to advance in weakly institutionalized and personality-centered coalitions, in which insider ties and financial power are often more important than ideas of ‘ policy or record of community leadership. Odinga’s nomination of the prominent female politician Karua as his deputy presidential candidate, although significant, does not change this wider pattern of political exclusion.

Furthermore, as other analysts have noted, a recurring pattern of collusion between political insiders also serves to protect the economic and political power of a narrow elite class, while undermining more meaningful forms of political accountability. Politicians have incentives to mobilize voters to secure their place in elite bargains; but once those bargains are struck, the needs of communities tend to fall by the wayside at the expense of elite interests. This trend helps explain why inequality in the country has spiraled: according to Oxfam, “the number of super-rich in Kenya is one of the fastest growing in the world,” with ” less than 0.1 [percent] of the population . . . own more wealth than the bottom 99.9 [percent].”

Against this background, politicians’ promises to tackle corruption are somewhat empty. For example, despite Kenyatta’s repeated promises against corruption, his own family’s hidden fortune only grew during his two terms in office, shielded from public scrutiny in offshore companies. His two potential successors are billionaires themselves, backed by networks of influential business elites. Given Odinga’s political alliance with Kenyatta, it is unlikely that a government led by Azimio La Umoja will seriously investigate graft allegations surrounding the Jubilee Party-led administration. Ruto, meanwhile, anointed Gachagua (member of parliament and former personal assistant to Kenyatta) as his deputy, even though the latter was implicated in an ongoing corruption investigation. In short, although devolution has opened up new spaces for citizens to exercise political agency and vote out local leaders who fail to deliver, deeper reforms—such as addressing widespread graft, growing economic inequality, and entrenched regional inequalities— remain difficult in a system in which. the same group of senior politicians (mostly men) govern to protect their own interests.

Recurring Electoral Concerns

Widespread distrust in Kenya’s electoral institutions reinforces the uncertainty created by shifting elite alliances, as the problems that plagued past elections have not been fully resolved. However weaknesses in electoral preparation are not simply capacity problems. To see also : At the ECOWAS Summit – United States Department of State. Instead, they are emblematic of a broader pattern of political interference with state institutions designed to check the power of the executive branch.

In the run-up to the 2017 polls, the IEBC adopted a new electronic voting system—the Kenya Integrated Election Management System—which was designed to facilitate voter registration and identification biometrics, the registration of candidates, and the transmission of election results. However procurement issues, rushed preparations, and a lack of systematic testing of the voting system ultimately led to widespread problems in the transmission of results on Election Day. In a surprising move, the Supreme Court decided to annul the initial results of that year’s presidential election and ordered a do-over vote, arguing that the IEBC had “failed, neglected or refused to conduct the Presidential Election in a manner consistent with the dictates of the Constitution.” The crisis has severely weakened public confidence in the electoral process, particularly after Odinga and his supporters boycotted the do-over election. Electoral disputes also lasted at the subnational level, with some court cases dragging on beyond the election year. Not surprisingly, Afrobarometer data from 2019 therefore shows a significant trust deficit in the IEBC, with more than half of Kenyan respondents saying they trust the IEBC “a little” or “not at all” ( see figure 1).

However, despite these issues, many of the shortcomings identified in 2017 have yet to be addressed, a failure that raises red flags about the commitment of political leaders to ensure a smooth electoral process. On the one hand, the government initially dragged its feet to fully finance the budget of 40.9 billion Kenyan shillings that the IEBC had requested; the commission in turn blamed funding shortfalls for delays in launching its national voter registration campaign. The National Assembly continued to block campaign finance regulations drafted by the IEBC, and the commission’s rules against early campaigning were largely ignored. Most recently, legal action successfully thwarted the IEBC’s attempt to enforce a constitutionally mandated gender quota on party candidate lists. Delays in important IEBC appointments, last-minute attempts to amend electoral laws, and a lack of action to enforce integrity standards for candidates have further alarmed civil society groups monitoring the -elections. A few weeks before the elections, the plan for the secure transmission of election results on Election Day remains unclear, as the connectivity issues that led to widespread disruption in 2017 persist.

Low levels of confidence in the IEBC does not necessarily mean that large portions of Kenyans will not turn out to vote, particularly as voters will choose not only a new president but also their local representatives. However, as the example of the 2020 US election shows, the lack of trust in the electoral process can increase polarization and discontent if the elections end up being close or contested. In the long term, such a lack of trust can also fuel cynicism about democratic institutions and apathy towards reform, which can allow further abuses of power by those who seek to advance their own agenda.

Moreover, recurring weaknesses in election preparation—and last-minute changes to electoral rules—reflect a broader pattern of underinvestment and political interference in Kenya’s oversight bodies. Leaders who stand to benefit from the continued centralization of political power have repeatedly tried to undermine the institutional checks and balances established by the 2010 constitution—such as the judiciary, parliament, and the Office of the Auditor General. Under Kenyatta’s leadership, for example, the government routinely ignored court orders, delayed the appointment of new judges, and slashed the judiciary’s budget. For example, he refused to swear in forty-one new judges recommended by the Judicial Service Commission, despite two court orders asking him to do so.

Of course, one could argue that the ongoing power struggles between the judiciary and the executive are a sign of democratic deepening, with the judiciary pushing back against the excesses of the executive rather than simply being predicated on presidential interference. . To strengthen Kenya’s democracy beyond episodic elections, it will be crucial to further strengthen the institutions that serve as a bulwark against executive dominance.

Heightened Economic Discontent

Finally, the August 2022 elections are being held amid widespread economic discontent, with many Kenyans concerned about food insecurity, unemployment, and the rising cost of living. Economic concerns dominated the electoral agenda. Read also : Finley: Stop making politics a crime. At the same time, there are also signs of disillusionment among Kenyans who doubt that campaign promises will produce tangible change, with young people in particular disengaging from the electoral process.

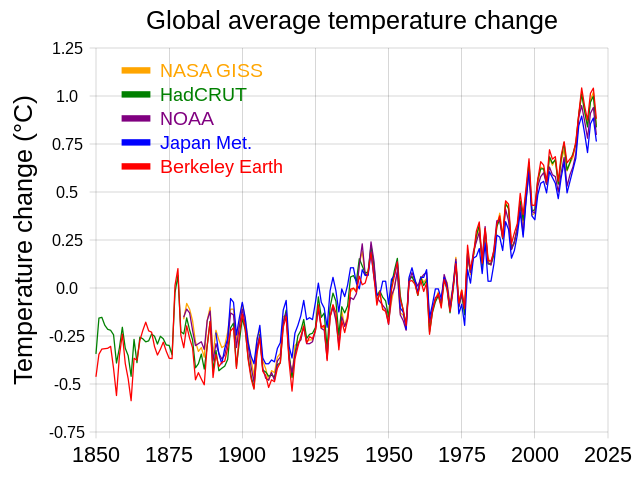

On the surface, Kenya’s economic outlook may not seem particularly alarming. Although many Kenyans have lost their jobs during the coronavirus pandemic, the World Bank expects Kenya’s economic performance to recover to pre-pandemic levels in 2022 (see figure 2). However not all Kenyans felt this recovery. Poverty is still above pre-pandemic levels, reinforced by severe drought in several regions of the country. Moreover, several worrying economic trends predate the recent crisis. The large-scale infrastructure projects that the government has undertaken over the past decade have not produced significant numbers of good-paying jobs, especially for Kenya’s young population. Census data released in early 2020 showed that 38.9 percent of Kenyan youth were unemployed, including many university graduates. At the same time, the country’s public debt has increased dramatically over the last decade, from around $16 billion in 2013 to around $71 billion at the end of 2021.

The cost of living for many Kenyans also continues to rise. Last year, the government imposed tax increases on basic commodities such as oil and cooking gas as well as on mobile phone and data usage. Since then, the prices of various food items have continued to rise, a trend that is particularly affecting low-income families. The conflict in Ukraine has exacerbated the problem, as Kenya imports about a third of its wheat from Russia and Ukraine. In addition, Kenyans are now also facing record high fuel prices and intermittent fuel shortages. Recent Afrobarometer polling data reflects these trends (see figure 3). The economy is now the number one priority that citizens want their government to address; in contrast, back between 2014 and 2019, it was sixth in the citizens’ priority list. Notably, only a small minority of Kenyans say the government is doing “fairly well” or “very well” in “creating jobs” (14 percent), “improving the living standards of the poor” (16 percent), or “manages the economy” (17 percent).

As a result, economic concerns are shaping the electoral agenda more than in previous years, with each camp seeking to draw up a plan for change. In some ways, the election is thus testing the narrative that Kenyan elections are shaped solely by ethnopolitical interests and affiliations. At the subnational level, past elections show that citizens’ assessments of government performance play an important role in election outcomes; politicians who fail to deliver direct services to their constituents are often voted out. But even at the national level, it is likely that a greater number of Kenyan voters, especially young ones, will consider their personal and economic prospects of the country to determine if and for whom they will vote.

For example, despite recent polling data showing Odinga building a narrow lead, Ruto appears to have benefited from widespread popular discontent. By casting the vote as a battle between Kenyan political “hustlers” and “dynasties” and contrasting his humble origins with the elite upbringings of Kenyatta and Odinga, Ruto’s campaign gained traction with many voters young people, even though Ruto himself is hardly a political outsider. He focused his campaign around a bottom-up economic model based on investments in small businesses, farmers, and informal workers. Odinga’s alliance with Kenyatta, on the other hand, (ironically) made it more difficult for the former opposition leader to distance himself from the incumbent’s record. He countered Ruto’s messages by promising to strengthen Kenya’s manufacturing sector, expand social protections (through direct monthly cash transfers to needy families), and launch programs new jobs creation, among other priorities. However, neither campaign has so far offered detailed proposals that can be realistically funded and implemented, particularly in light of Kenya’s debt burden. Many of the policy areas highlighted in public statements, such as skills development or ending corruption, have also featured prominently in past campaigns, with little or no substantial follow-up.

This model speaks to a wider challenge, namely a persistent disconnection between electoral democracy and the lived reality of many citizens. Many young people in particular have grown wary of unfulfilled campaign promises—such as those made by Kenyatta and Ruto in 2013 and 2017—even as corruption runs rampant and the cost of living continues to rise. . The argument that voting counts, one typically made by older generations to younger ones—is becoming less convincing to those who voted but saw little change. A growing sense of disillusionment with electoral politics may help explain why mass voter registration campaigns launched in October 2021 and again in January 2022 have failed to meet their targets, with -IEBC registers only 12 percent of the estimated 4.5 million potential youth voters. Although these problems were partly driven by poor planning, they also suggest a wider pattern of disengagement among the country’s youth, who do not identify with any of the main candidates or are not convinced that the election will bring significant change. .

What’s Next for Kenyan Democracy?

There are different ways of assessing Kenya’s democratic trajectory. An optimist can point to a tendency of gradual institutionalization, continuous demands of citizens for accountability and better governance, and the repression of the judiciary against the excesses of the executive. At the same time, the country is still facing real democratic challenges. Transactional elite bargains are weakening democratic participation in the political process, while electoral institutions are still struggling to assert their credibility and power vis-à-vis politicians and political parties, which can create challenges in ‘a close election. The electoral competition did not ensure significant accountability for abuses of power, an issue that risks fueling disillusionment with democratic politics.

Most Kenyans are however desperate to ensure minimal disruption to the electoral process, regardless of the outcome of the August 2022 vote. Many voters feel wary of renewed bouts of violence and instability that would further undermine the economy of the country and are unlikely to result in political change. Instead, socio-economic concerns and demands for solutions are likely to dominate the elections. As a result, there can be widespread voting of leaders who citizens feel have not kept their promises, even as the institutionalized means of holding elected leaders accountable have been weakened. However, although economic issues were more prominent during this campaign season than they were in the recent past, the real and very urgent problems faced by voters are hardly in focus, beyond the slogans and promises of -campaign. This will present a major challenge to any candidate or coalition that gains power, as different socio-economic crises merge in the country.

International actors invested in Kenya’s political trajectory have tended to focus on preventing renewed electoral conflict, sometimes at the expense of other democratic challenges. The fact that the Supreme Court annulled the 2017 presidential elections, which were considered free and fair by international observers, undermined the credibility of the international community among Kenyan voters, who had experienced an election full of problems and irregularities . Kenya’s current political environment emphasizes once again that elections alone are an important, but not sufficient, indicator of democratic progress. Instead, regardless of the outcome of the August election, it will be crucial to focus on strengthening democratic and institutional performance, political accountability, and citizen participation beyond Election Day. Subsequent events in Kenya may well show how important this awareness is around the world.

This article is part of the Pivotal Elections in Africa series jointly produced by Carnegie’s Democracy, Conflict, and Governance Program and the Africa Program.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the opinions represented here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.