Zeeshan Nabi, a Kashmiri musician and singer, records music in his studio on the outskirts of Srinagar, controlled by the Indians of Kashmir, June 13, 2022. Musicians and artists in Kashmir are ordinary in life, each embracing the lived experiences of growing up in one of the most militarized zones a world that has experienced nothing but conflict for decades. But together they embody a new form of music, a mix of progressive rock and hip hop that is an assertive expression of the region’s political and cultural aspirations. (Photo AP / Dar Yasin)

Sarfaraz Javaid rhythmically slaps his chest in the music video, swaying to the guitar and letting his throaty voice echo through the woods: “What soot covered the sky? entrusted to strangers?

“Khuaftan Baange” – Kashmir for “call to night prayer” – plays like a wailing lament to the Muslim majority of Kashmir, a beautiful Himalayan territory that is home to decades of territorial conflict, soldiers armed with weapons and severe repression of the population. It is mournful in tone, but rich in lyrical symbolism inspired by Sufism, an Islamic mystical tradition. Its form is Marsiya, a poetic interpretation that laments the Muslim martyrs.

“I just express myself and scream, but when you add harmony it becomes a song,” the poet Javaid said in the interview, as were his father and grandfather.

Javaid is part of an artist movement in contested Kashmir, split between India and Pakistan and embraced by both countries since 1947, who are creating a new musical tradition that combines progressive Sufi rock with hip-hop in an assertive expression of political aspirations. They call it “conscious music.”

Relying on elements of Islam and spiritual poetry, it is often intertwined with religious metaphors to circumvent measures restricting free speech in Indian-controlled Kashmir that has led many poets and singers to swallow their words. It is also trying to reduce the tensions between the Muslim tradition and modernism in a region that in many ways still clings to a conservative past.

“It’s like venting decades of suppressed emotions,” Javaid said.

Kashmir has a centuries-old tradition of spoken poetry that is heavily influenced by Islam, with mystical, rhapsodic verses often used in supplication in mosques and temples. After the outbreak of the rebellion against Indian rule in 1989, poetic messages about liberation poured out of the mosque’s speakers, and elegies inspired by historical Islamic events were sung at the funerals of fallen rebels.

Two decades of fighting left Kashmir and its people maimed by tens of thousands of civilians, rebels and government forces before the armed struggle died out, paving the way for the mass unarmed demonstrations that rocked the region in 2008 and 2010. the rise of protest music in English-language hip-hop and rap, a new hymn of resistance.

Singer-songwriter Roushan Illahi, who goes by the stage name MC Kash, pioneered the genre by creating angry, neck-grabbing music that has become a call for young people to use sharp rhymes and beats to challenge India’s sovereignty over the region.

However, Kasha’s songs came dangerously close to revolt as it is illegal to challenge India’s claims to a troubled region. The country has drastically restricted freedom of expression related to the Kashmir problem, including restrictions on media, dissent and religious practice.

Frequent police interrogations led Kash to the point where he almost stopped making music. Some colleagues are still recording and performing, but have started to use coded language or have deviated from politics altogether.

“At first it was a choke,” said Kash, “but now it’s a pillow on the lips.”

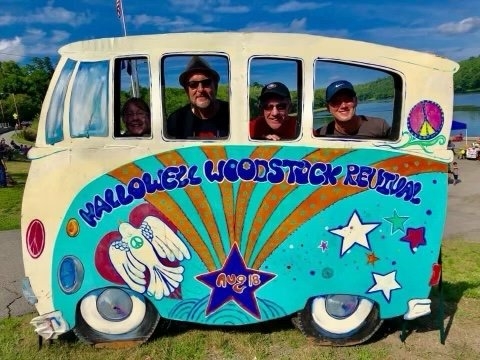

Last afternoon, a group of young artists gathered at the home studio of the composer Zeeshan Nabi in the suburbs of Srinagar, the main city of Kashmir. Filling the room with puffs of cigarette smoke, they passionately debated the essence of metaphors and religious references in their work.

“What (religious symbolism) does is keep knocking on the door, either as a reminder or as a memory of the past,” said Nabi.

He expressed optimism that the gag was temporary: “How long can you hold on to? The persecutor may oppress for a certain time. “

“We are dreamers,” said Arif Farooq, a hip-hop artist who uses the stage name Qafilah, laughing.

Qafilah’s music video “Faraar” – “Fugitive” – begins with a harmonica wire shot and he sits in the temple courtyard in honor of Kashmir’s most revered Sufi saint, Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani. It evokes the ancient Battle of Karbala in which the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad was martyred and which symbolizes the fight against injustice and oppression.

“Our disease can only be cured by revolution, my friend. Every answer lies in Karbala, my friend, ”exclaims Qafilah in the song.

Religious symbolism, said Qafilah, is a creative tool that reflects the pain of Kashmir and also avoids the state’s gaze.

“You want to steal, but you don’t want to get caught,” he said.

In this new musical form, it is difficult to overlook the symbolism of faith as a subtext.

One of the recent films, Inshallah – “God’s Will” – features texts that evoke monotheism, the cornerstone of the Islamic faith. Singer Yawar Abdal envisions Kashmir in which people with blindfolds and loops around their necks are released amid singing “All will be free”. The “inshallah” chorus is set against a thunderous chorus of morning prayers sung in mosques.

Another song – “Jhelum”, named after the main river of Kashmir – became an instant hit, contrasting the banality of everyday life in Kashmir with the ongoing mourning for the dead. Since then, in online videos, users have set the song on moving and still images of fallen fighters to commemorate them – this is in part a way to counter the authorities’ policy from 2020 of burying suspected rebels in remote mountain cemeteries, preventing their families from performing the last rites .

“It’s the tension in the air that shapes you in a certain way,” said the poet and singer Faheem Abdullah, the man behind Jhelum.