Jason Dunion, an associate scientist at the University Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies, University of Miami, is heading a 2022 storm field program that will test new aerial drones capable of flying at altitudes that are considered unsafe for Hurricane Hunters and other reconnaissance aircraft.

As a child, Jason Dunion would attach a portable weather station he received for his eighth birthday to the front door of his New England earth, take temperature and humidity readings and record storm broadcasts that affected his community.

Today, as a scientist at the University of Miami Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS), Dunion still measures storm dynamics. But the instrument that is currently being used to study is the quantum leap above the childhood weather station.

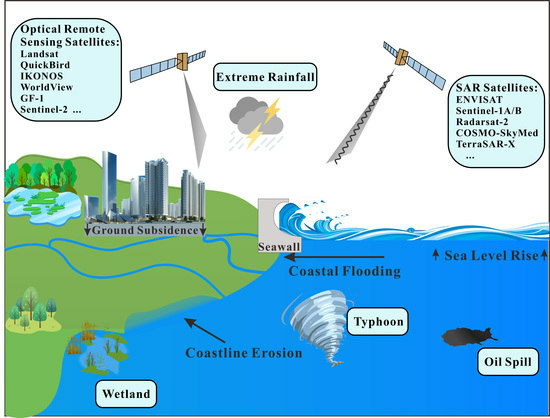

From powerful radar systems that provide detailed data about winds near the eye wall of tropical cyclones to drones that fly below 100 feet above sea level that provide information about critical air-sea interfaces, Dunion uses many high-tech tools. to help scientists solve some of the storm mysteries.

The devices work on Hurricane Hunter aircraft that fly into the heart of the storm, providing the critical information needed to build reliable forecasts and models. And this year, as part of Dunion’s new role as director of the Hurricane Field Program — a collaboration between CIMAS, which is part of the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, and the Hurricane Research Division of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration — he will oversee their flight missions, which use highly modified Orion P-3 aircraft and high-flying, high-speed Gulfstream IV jets.

Doppler radar is a lynchpin on that flight. “Most of us know about the deep core of the storm because most satellites can’t see through the cirrus cloud canopy above,” Dunion explained. “But Doppler gave us an X-ray shot of how the storm winds in the core, up to almost sea level up to the top of the storm system, as high as 50,000 feet.”

Radar clarity has helped predict storm forecasts, making many models better at predicting storm intensity. “It’s a real game changer,” Dunion said.

He has flown on about 60 Hurricane Hunter missions, flying directly into storms like Dorian, Irma, and Sally — eight-hour sorties he describes as intense roller-coasters.

“The eye wall, which is outside the eye, has the worst weather and the highest cloud peaks. And that’s usually where you’re going to see the strongest winds,” Dunion said, noting that the scientists on the flight can experience as many as four forces G, which is larger than that borne by astronauts at the launch of NASA’s Space Shuttle.

“We are tied, and we can lose or receive a height of a few hundred feet in just a few seconds. And at the same time, we work with radar and deploy dropsondes [devices],” Dunion said. “But just inside that wind field is that Strong is the eye of the storm, where it is very calm. You can completely unpack and get out of your seat. ”

Of the dozens of missions that he undertook, flights to the teeth of Hurricane Dorian in early September 2019 were worse.

“When the storm got close to the Bahamas, the situation was ripe for improvement. At the same time, the steering current was broken, and the forecast was only flying in the Grand Bahamas,” Dunion said. “We flew into the storm, and at one time, updraft around. four G. I feel like a feather in the wind. That’s a strong Category 5 when we get into the eye. The cloud tops were probably up close to 50,000 feet, and we’re not going over the top of the storm; we plow in the middle. “

With storms becoming stronger and with the past few hurricane seasons presenting activity above normal, improving tropical cyclone forecasts and modeling through instrumentation becomes more crucial, Dunion asserts.

While Doppler radar, dropsondes, and other devices will continue to be stalwarts of storm information collection, other devices such as drones are quickly emerging as next-generation storm reconnaissance. And this summer, Dunion helped to lead a NOAA field program that will test a new class of aerial long -range drones designed to fly at altitudes too dangerous for aircraft: only a few feet above sea level.

Dropsondes, which are removed from the plane and stabilized by a small parachute, offer briefly what is happening at that level. “But that’s only a snapshot of what we want to know,” Dunion said. “It can be dangerous to fly too low, and we don’t want to fly low into a storm like Dorian. But we can fly a drone at that height, close to sea level which is very important. That’s where all the energy from the ocean is transferred to the atmosphere, directly at that interface.

If tested well, drones will be launched into several storms this winter in the Atlantic.

Dunion will also help test the new Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) system, which provides a new way to measure wind speed. “It has incredible potential,” he said. “To measure wind using Doppler radar, you need rain spots. But LiDAR wind can measure wind in clear air because they see the molecules in the air that are moving. It will let us know not only about the wind in the inner core but also which is on the periphery.

He will also continue his own area of research: remote sensing satellites of hurricanes, which have led to the development of new instrumentation to monitor tropical cyclones and Sahara ash storms and predict the genesis of hurricanes.

Dunion recently received the Richard H. Hagemeyer Award for significant long -term contributions to the advancement of research on storms.

“And just think,” Dunion said. “That [career] all started with a little weather station that I wanted as a birthday gift.”