Ten artists tell us about a key book they read this year and how it influenced their practice. — Ed.

We love this book so much. Its streamlined layout and clear, methodical style allow you to swim around inside it. Although we are not architects, we like to use this book as a lens to see ourselves as artists and recreate the function of art making. Rather than seeing artists as isolated vehicles of their own genius, this book portrays them as conveying a collaborative energy for all and sundry. For us, making a good work of art is like building a world. This book gives us the courage to pursue beauty and truth and create a world that poetically contains what Alexander calls “the fire of self-maintenance, which is the quality without a name.”

A throwback to the endless summers of childhood, to frolic with wild abandon, full of honeysuckle dew, heavy humid air and the feeling that comes from unleashed reins.

Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments is not that kind of coming-of-age story, but a celebration of early 20th century black women who lived as if they were free. Saidiya Hartman, a cultural historian, weaves together intimate fictional portraits of “surplus women of no consequence” who went largely unnoticed by history. Gathering the few archived traces written by debt collectors, parole officers, and psychologists, she illustrates the lived realities of these women as evidence of the social upheaval that transformed black lives during that period. Idle, shifting and wanted, too smooth to define, these wayward women remain revelations, invisible givers and shapers of black life and dreams.

Last year I taught a class with scholar Lisa Vinebaum and artist Ebony Patterson called “Making in the Aftermath.” Sharing Hartman’s text with our students catalyzed honest and compassionate reflections on their own family history, both told and untold. Wayward Lives is timeless and contemporary.

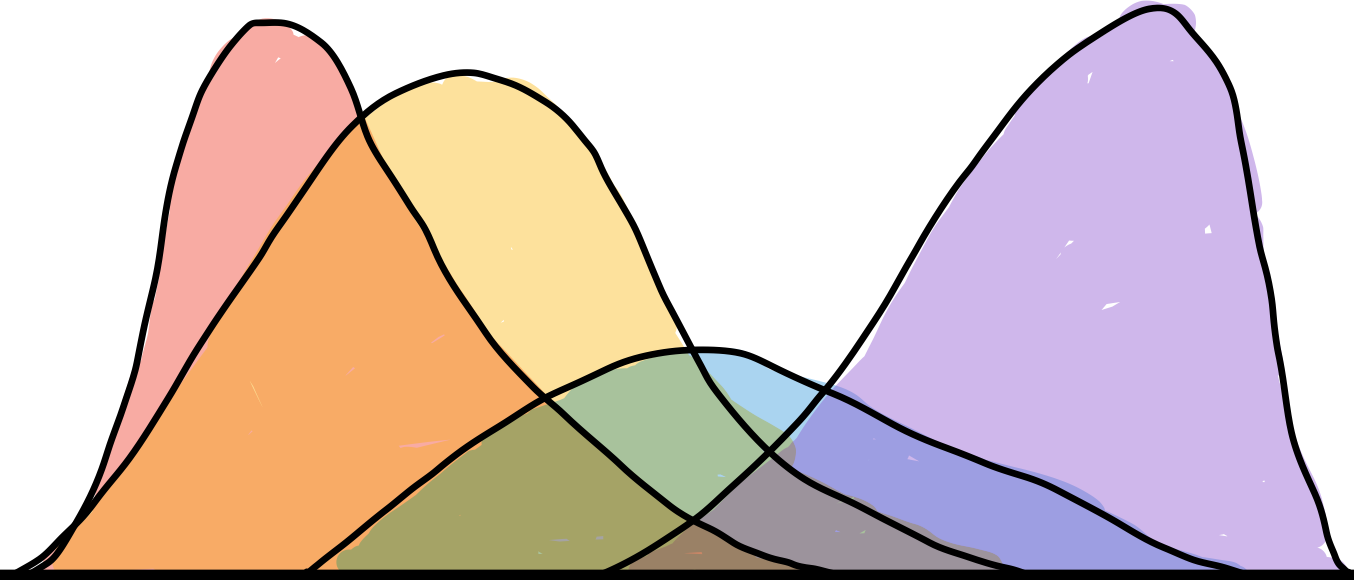

In Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology, cultural theorist Astrida Neimanis considers how water connects us to other people and to other species, as well as to the bodies of water that surround us all. She calls these shared conditions to water our “hydrocommons”. Bodies consist of this matter which existed before bodies existed. Your water is the same as mine inside, but we are very different people. Skin both connects us to the outside world and separates us from it. In my own work I use water as material and poetics and politics to question conventional modes of representation – thinking about the queer and trans body, or the liquid body, in relation to the containers of the bathtub, the swimming pool, the lake, the sea. I am interested in how science expresses what or who belongs where, and what constitutes the boundaries of a body or a body of water, and who distinguishes between inside and outside.

I often get stuck when I think about how poor the glyph, the line and the page feel in the face of speech. And then something comes to loosen me up: This year it was the work of poet-playwright Aleshea Harris, whose screenplays Is God Is (2016), What to Send Up When It Goes Down (2018) and On Sugarland (2022) ) are accurate and generous. As a student, Harris studied with the brilliant poet, librettist and performer Douglas Kearney, who often uses innovative typography in his knotty, dense, visual poems. Harris lets letters stumble and drip from one line to the next, like a fountain or a sundae or a chandelier. Words crescendo and bulge, overlap and collide and spark and make heat. In Is God Is, “I don’t rem / member / ber” appears in a font so diminished that I myself shrink. “Every piece of / p u z z l e? / What other pieces are there?” The cheeky one! So much action compressed into so little. This spring, at the New York Theater Workshop, I saw On Sugarland, in conversation with Sophocles’ Philoctetes. Epic and inspiring. I can’t wait to see it in print.

I picked up The Lie That Binds in the wake of Amy Coney Barrett’s hasty confirmation to the Supreme Court, with the uncertain fate of Roe v. Wade looming. I had been researching abortion rights for a new work, and I turned to this book, among others, expecting an informative but possibly rather dry examination of the struggles for and against abortion rights in recent US history. Instead, I found myself completely engrossed in one of the most coherent and compelling analyzes I have yet read at the intersection of sexual and reproductive-health rights and issues of race and class. Looking at many facets of the civil rights movement, including school desegregation, tax policies, and the Voting Rights Act, the book charts the shifting cultural and political fault lines that helped turn opposition to abortion into a byword for fervent conservative orthodoxy.

In the early morning hours of March 29, 2020, the sound of an ambulance woke me up. I made a post on my Instagram with a video recording of the street view from my window. The caption read: “It’s 6:30am. I haven’t been outside for a week. The birds are singing, reminding me of this question from a poem by Alice Walker, ‘What do birds think/of/us?'” Walker’s book of poems Hard Times Require Furious Dancing is often with me. She urges fierce healing to survive our cataclysmic moment. Walker reminds us that “each of us is proof” of this requirement and advises: “What waste/is any kind of /agt.” The truths and affirmations that I find in poetry are the seeds of inquiry in my practice.

Stories of Almost Everyone is a collection of twenty-nine short essays that consider the narratives that objects hold and the failures of institutions and others who speak on behalf of objects. The book was published alongside the eponymous exhibition at the Hammer Museum.

As an artist who spends a lot of time thinking about objects, I appreciated the different ways contributors approached the conversation: philosophical, historical, critical, intimate. Poet CAConrad’s piece – about the unthinkable rape and murder of their lover and the ritual they performed (using two quartz crystals) to save themselves from consuming grief – brought me to tears when I first read it, and it continues to haunt me. Beyond the horror of hate crimes and violence in our country, this particular text captures the timeless logic of an individual’s need for ritual (and a ritual’s need for objects).

Other texts—by Ikechukwu Onyewuenyi, Chris Kraus, and Charles Ray—have also stuck with me, and I keep this book in my study to reread when I need to.

ʿAṣfūriyyeh was one of the first psychiatric hospitals in Lebanon. When it was founded in 1896, it was a symbol of the modernization of the medical sector. But it was stigmatized and by the time I was born, in 1983, it had closed down. It existed for years in my imagination until my freshman year of college in Beirut when I got to visit the place. It was a modern ruin, a time capsule on top of a hill overlooking the city.

Joelle M. Abi-Rached’s account of ʿAṣfūriyyeh balances a clinical approach to history and a subjective desire to analyze this site to understand Lebanon’s past and present conditions. I am interested in such places because of their potential for not only investigation but reinterpretation. You can insert yourself into their story, influence the way they are remembered. I now realize how much this place has informed my practice. I find myself in the middle between fantasy and reality, and with both I can actually do something.

Shame and guilt motivate Ahzek Ahriman, a 10,000-year-old sorcerer from Old Earth’s Iran, on his journey through deep space in the distant future. John French’s Ahriman: The Omnibus would be a relatively standard space opera, except for the fantastic descriptions of metaphysical travel and violence.

Utterly old and utterly immature, Ahriman surrounds himself with others of his kind: demons, artificial intelligence builders, striking swordsmen, mystical artillerymen, and hollow ghosts. Spanning the astral, psychic, and physical realms, these characters wage ugly and humiliating battles with themselves, their brothers, and the psychic afterimages of their dead and eaten enemies that live on in their brains.

It’s fascinating to read a story about posthumans, irrevocably inhumanly dehumanized sentient beings who try to use their tacky magical practices to make themselves feel human and “normal” again, ways of being they can barely remember .

This book is a compelling portrait of musician and composer Ornette Coleman told through the economic and sociopolitical history of his hometown of Fort Worth, Texas. Although Coleman always seems to have been on the fringes of the city’s music scene (he was kicked out of his high school band for improvising over Sousa’s “Washington Post”), it seems the city was supportive and inspiring enough to shape him and a string of local musicians who would make important contributions to the field of so-called jazz.

Aside from its historical content, this book has had a huge impact on my thinking about “sonic territory”, the sounds and music specific to a region or locale. It helped me formulate a body of work that recognizes the Texas Trinity River basin as an important sonic territory in American music. It is the birthplace of many heavyweights – not only Coleman, but also Blind Lemon Jefferson and Sly Stone.